Monitoring Ritual Hunting in 2023

India’s rich natural heritage is reeling under the pressure of habitat loss and unmitigated urbanization. In West Bengal, the ongoing struggle to conserve wildlife is worsened by ritual hunting festivals – a mass wildlife crime of epic proportions. Thousands of wild animals in the forests of South Bengal are slaughtered by armed hunters annually during these festivals. HEAL has been working for the past eight years to bring an end to this vile practice using legal intervention, law enforcement, activism and meticulous field investigation.

HEAL has tirelessly strived for the past eight years to put an end to the abhorrent practice carried out under the guise of ‘traditions’. We have filed multiple Public Interest Litigations, leading the Calcutta High Court to issue directives to the West Bengal state in April 2019 to actively halt ritual hunting. Additionally, we have meticulously documented every hunting season since 2016 and worked closely with state authorities to ensure the implementation of Court orders on the ground.

Through diligent Court order enforcement and proactive preventive measures adopted by enforcement authorities, we have achieved significant success in mitigating the Faloharini Kali Pujo hunt fest, an annual event in East Medinipur and Howrah. Unfortunately, systemic inertia continues to obstruct the successful implementation of Court orders in Purulia, Bankura, Jhargram, and West Medinipur, preventing a similar reduction in the scale of hunting festivals in the Jangal Mahal belt.

Below is an account of our experience this year while monitoring the ritual hunting festivals in several districts of South Bengal.

The February 2023 Order

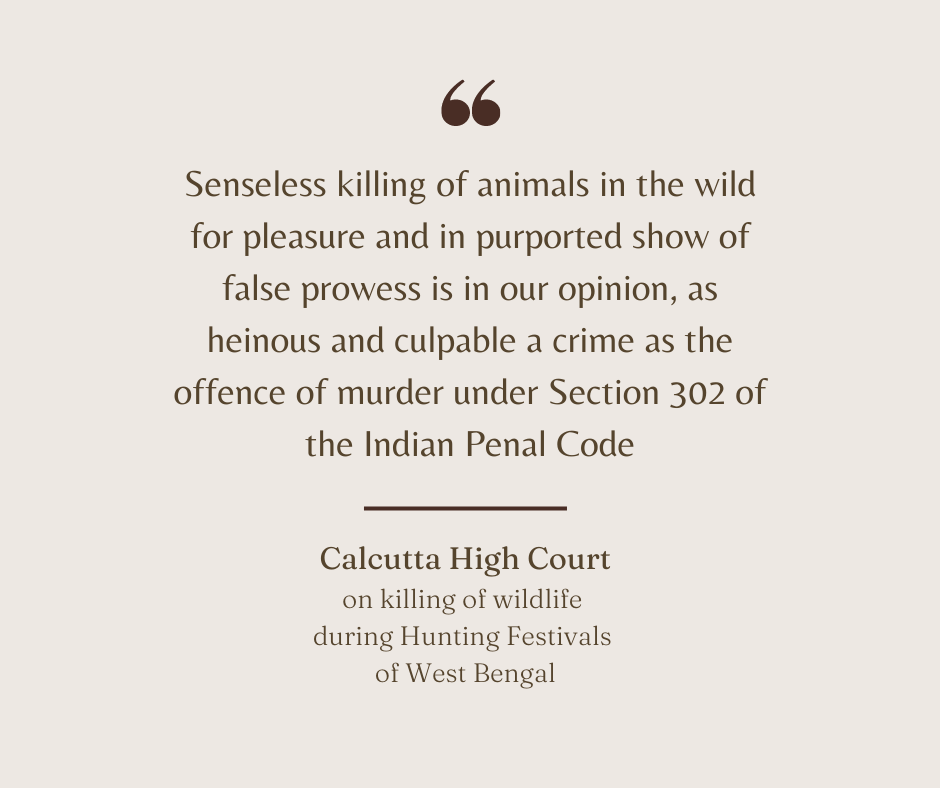

Unsatisfied with the lack of action by state authorities in Purulia, Bankura, Jhargram and West Medinipur during the hunting seasons of 2021 and 2022, HEAL filed a Contempt Petition against West Bengal’s Chief Wildlife Warden, as well as the Railway Department, Civil Administration, and Police Department of the mentioned districts in June 2022. These contempt proceedings led to a landmark judgment by the Calcutta High Court on February 20, 2023.

In the order, the High Court equated the senseless killing of wild animals during hunting festivals to the heinousness of human murder. Furthermore, it mandated the establishment of Humane Committees in Purulia, Bankura, Jhargram, West Medinipur, and Murshidabad, entrusting them with implementing the April 2019 order that prohibits hunting festivals and directs state authorities to intervene.

Chaired by the District Judge, these Committees are convened by the District Legal Services Authority (DLSA) of each district and include the District Magistrate, Superintendent of Police, Senior Railway Officials, and Divisional Forest Officers. Eminent conservationist, ecologist, and HEAL’s Joint-Secretary Tiasa Adhya is a common member among all Committees. Being a member of the civil society, Tiasa’s inclusion, ensures transparency in the Committees’ operation and enables HEAL to put forth matters of wildlife conservation before the highest offices of the government machinery.

All five Humane Committees began operating in March 2023. Each Committee presented a comprehensive Plan of Action to the Calcutta High Court, outlining measures to prevent ritual hunting and wildlife killing in their respective districts. These measures encompassed actions throughout the year, a month prior to the hunting season, and on the D-Day of the hunt fests, aiming for effective April 2019 order implementation.

Hunting Festivals of Jhargram, West Medinipur, Bankura and Purulia in 2023

In the weeks leading up to hunting festivals, the DLSA and Forest Department conducted vigorous awareness campaigns in villages and tribal hamlets, emphasizing the illegality of ritual hunting and the importance of wildlife conservation. While these efforts helped raise public awareness on wildlife conservation laws, the state authorities’ actions proved inadequate in thwarting hunting festivals. This inadequacy primarily stemmed from enforcement authorities’ failure to adhere to the agreed-upon Plan of Action and execute preventive measures.

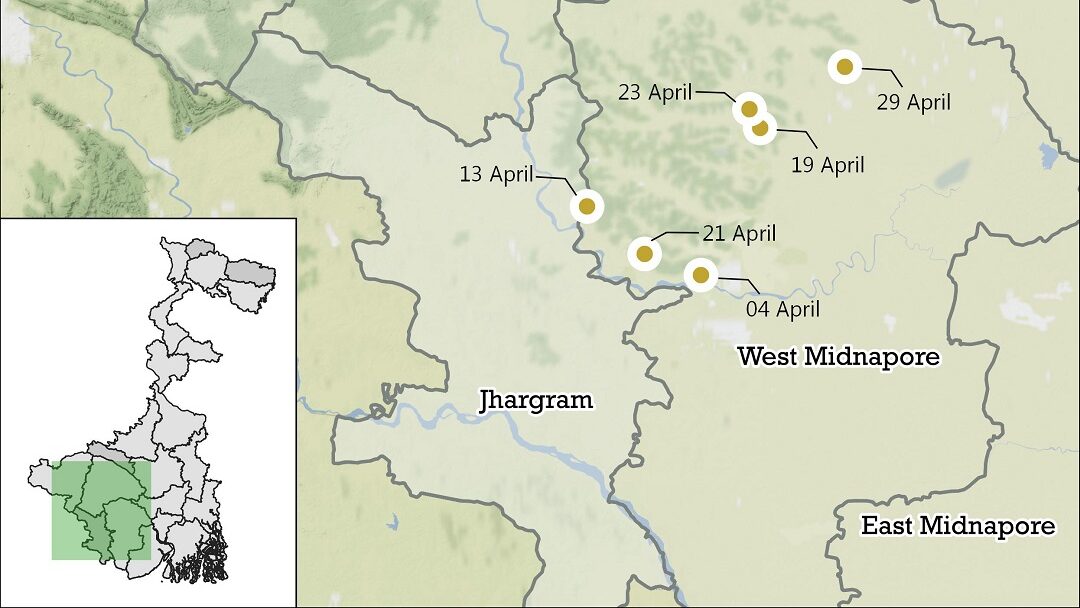

During all hunting festivals, police checkposts remained unmanned until 7 am, by which time most hunters had already gathered at hunting sites. This absence of functional checkposts posed a significant problem during large-scale festivals on 04 April, 13 April, 19 April, 21 April, and 05 May, as it enabled hunting parties from other states like Jharkhand to enter South Bengal in massive numbers without much difficulty.

Once inside the forests, hunter groups vastly outnumbered enforcement authorities, who were deployed in insufficient numbers. Exploiting this, the police used this as a justification for not stopping hunters or confiscating their weapons at the checkposts near hunting locations. Consequently, armed hunters operated with complete impunity, while authorities looked on. Weapons were seized only during two hunt fests – on 04 April in Gopegarh and 13 April in Pakhibandh – following relentless urging from our volunteers. On smaller hunts, police checkposts were entirely absent.

As in previous hunting seasons, hundreds of wild animals were hunted in blatant violation of Court Orders. However, detecting the evidence of hunted wildlife proved more difficult this year, as hunters, now aware of the illegality, surreptitiously transported their kills home instead of displaying them openly. We also noted hunters using cautionary campaigns in their local Olchiki language during hunt fests, warning others of our presence and advising them to conceal kills under Sal leaves while traversing the forests.

Nevertheless, we documented at least 30 kills during multiple hunt fests, including species protected under Schedule I and Schedule II of the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972, such as the Indian Hare, Mongoose, Monitor Lizard, Small Indian Civet, Jungle Cat, Golden Jackal, and Wild Pig. Local informants suggest the actual kill count is likely higher.

Efforts to photograph or video-record kills or the hunt fest were met with aggression. Our team members courageously captured images and videos of killed wildlife, serving as crucial evidence to refute state authorities’ claims of no hunting within forests. In two instances, we managed to apprehend hunters with poached wildlife – on 04 April during the Gopegarh hunt fest and on 19 April at the Arabari hunt fest in West Medinipur. However, the West Medinipur Police Department displayed strong resistance to arresting hunters or filing FIRs against them, emboldening the hunters further.

The hunters’ lack of fear of retribution is exemplified in their behaviour towards our team on 13 April 2023 during the Pakhibandh hunt fest in Jhargram. Taking advantage of the Jhargram and West Medinipur Police Department’s inaction, hunters gathered freely in alternative locations while their usual congregation ground in Pakhibandh was cordoned off. When our team arrived at the alternate location for evidence collection, the hunters launched an unprovoked attack. Fifteen of our team members were assaulted, their vehicles vandalized, and personal belongings stolen. Our team managed to escape and reported the incident to the authorities.

Based on the first hand experience of our field teams who were present on the ground during the hunt fests, we prepared detailed field reports and submitted them to the Jhargram, West Medinipur and Bankura Humane Committees. These independent reports provided an accurate account of state authorities’ progress in implementing Court orders and curbing ritual hunting in 2023. After the attack on our team, we submitted an application to the Calcutta High Court, highlighting the deliberate inaction of the Paschim Medinipur and Jhargram police authorities.

During a hearing on April 28th, HEAL’s Senior Counsel argued that the police in these districts had neglected Court orders, enabling hunters to engage in wildlife hunting without consequence. Moreover, their failure to control unlawful gatherings of hunters within forests contributed to the attack on our team on April 13th at Pakhibandh. Responding to these submissions, the High Court directed the Superintendents of Police of Jhargram and West Medinipur to personally attend the next hearing on May 10th and address HEAL’s allegations. This directive underscored the judiciary’s commitment to mitigating ritual hunting. We remain optimistic that consistent pressure on authorities to enforce measures will yield positive long-term results, even if immediate outcomes are not readily apparent.

Hunting Festivals of East Medinipur and Howrah in 2023

Unlike the hunting festivals of the Jangal Mahal region, the Faloharini hunt fest was effectively controlled through impeccable coordination among government departments, non-profit organizations, and civil society members. Spearheaded by the Howrah and East Medinipur forest divisions, these efforts resulted in making this hunt fest virtually bloodless for a second consecutive year.

This year, the hunt took place from May 16th to May 19th. Typically, hunters from Jharkhand, Jhargram, Bankura, West Medinipur, and other locations arrive in East Medinipur and Howrah to participate in this hunt. Trains serve as the primary mode of transportation for these hunters. Consequently, they mainly target wildlife in peri-urban wetlands and agricultural fields located near railway stations. Such wildlife includes Jungle cats, fishing cats, mongoose, monitor lizards, snakes, and birds.

Prior to the hunt fest, the Howrah and East Medinipur Forest Divisions conducted meetings with the District Administration, Police, Railways, Excise Department, Block-level Administration, Gram Panchayats, and local non-profit organizations to formulate effective anti-hunting measures. During the hunt fests, collaborative teams comprising forest officials and volunteers from local NGOs, including HEAL, maintained round-the-clock surveillance at railway stations, ferry ghats, and strategic checkpoints along major roads to identify and intercept hunters.

Excise officials carried out raids in East Medinipur to seize illegal liquor during and immediately preceding the hunt days. Such raids were necessary to curb the illicit sale and distribution of liquor, which tends to attract gatherings of hunters, often near liquor shops. The Brick Field Owners Association cooperated in preventing migrant laborers from hunting, and awareness campaigns were conducted at railway stations and tribal settlements in Howrah and East Medinipur, further diminishing the scale of the hunt fest.

The Kharagpur Railway Division actively monitored railway stations in conjunction with volunteers from HEAL and other NGOs, effectively preventing armed hunters from boarding trains or alighting at destination stations. Approximately 250 armed hunters, a significant reduction compared to previous years, were apprehended. Their weapons and hired vehicles were confiscated by the Forest Department.

The successful mitigation of the Faloharini Hunting Festival stands as a remarkable testament to how seemingly daunting conservation threats can be resolved through the coordinated efforts of multiple stakeholders.