Raha, Raha, Raha!” urges Panchanan Nayak. The hoarse, urgent whisper from the short, wiry man makes the eight-foot tall elephant, the matriarch of the herd stop in her tracks. She grinds to a halt, then extends her trunk to encircle her young son, in her attempt to contain him. She is a wild elephant, even if Panchanan calls her by the name “Lakshmi”. Her herd of 25-odd-elephants have paused— impatient—just short of the busy Bhubaneswar-Athgarh highway (Odisha) and the paddy fields beyond.

It’s surreal: 25 wild elephants contained in their path by Panchanan or Panchu as he is known, and his three colleagues—Sanatan Nayak, Dileep Sahu, Santa Sahu—who form the “Athgarh Elephant-conflict Mitigation Squad”.

Squad is a grandiose title for Panchu and his gang, a rag-tag group of four daily wagers employed by the forest department and armed with nothing more than mobile phones to coordinate between themselves, call in forest staff for reinforcements, or police to control crowds.

Here man and beast communicated.

Not by force. Not by firing blanks, bursting crackers, or burning mashals (flame torches)—the methods usually deployed across India to ward off wild elephants as they enter towns, bazaars, and fields that were once forests.

It was late afternoon when the elephants approached the road. Traffic was at its peak, and people milled around: working in the fields, doing brisk business in the dhabas and shops that line the highway. Children were racing back from school, and cowherds herding their cattle back home.

On the edge of the road, barely hidden by a forest fragment, the elephants were restless. On the other side, was water (this is a dry landscape with scant water sources), and the paddy was ready for harvest—an easy, power-packed snack for the pachyderms. The small, patchy forests of Athgarh that the elephants are confined to do not have the forage to sustain them.

They are former Chandaka elephants, a sanctuary on the outskirts of Odisha’s capital, Bhubaneswar, whose rapid, ill-planned expansion fragmented it.

Chandaka forests were once contiguous to the Kapilas forest further north. Westwards along the left bank of the Mahanadi, they extended towards Narsinghpur, and into what is today the Satkosia Tiger Reserve and Mahanadi Elephant Reserve. Once upon a time the elephants traversed the entire landscape. Ancient instincts and knowledge dictates their movements, decides the paths they take. They know they must move to strengthen their bloodlines, and not to overburden a forest. One elephant consumes about two quintals of plants a day. They are not just copious consumers, but equally distributors of seeds which they disperse, smartly packaged in fodder—dung—as they travel, contributing, in a major way, to a forest’s plant diversity. Confining elephants in small islands, and pushing themto feed in fields, will slowly, but surely, wither a forest, as in the case of Chandaka.

A mixed sal forest, Chandaka represents the northern tip of the Eastern Ghats, not as celebrated as the Western Ghats, but equally rich in biodiversity. Chandaka had tigers once, with the last resident recorded in 1967. Even as the big cat vanished, it continued to harbour other rare species—elephants, leopards, sloth bears, ratels, etc. It was declared the Chandaka-Dampara Wildlife Sanctuary in 1982, to protect elephants—it had over 80 till 2002 in its 190 sq. km—and serve as Bhubaneswar’s green lungs.

Over time the dynamics of the city and the forest changed. From a quaint capital built post-independence in 1948, Bhubaneswar has grown rapidly with a vision to transform the Chaudwar-Cuttack-Bhubaneswar urban conglomerate into a metropolis that will replace Kolkata as the “hub of the east”. Gated colonies, large institutes (Bhubaneswar has over 100 engineering colleges, plus a number of management and other institutes), tech parks, hospitals and malls have come up, decimating and engulfing the sanctuary and its surrounding forests.

Even within the sanctuary there were problems. Chandaka was neglected and mismanaged—overgrazed by cattle, exploited for firewood, encroached by villages, it no longer offered refuge for its denizens. Pushed out, elephants raided fields, blundered into residential colonies and institutes that were once forests. Crackers, shotguns, crowds, mobs and mayhem invariably followed wherever they went. The desperate, bewildered elephants were on the run, hounded by mobs, harassed by hostile villagers. A few fell on the wayside: some from sheer exhaustion, some were poisoned, others electrocuted. Six including two calves were crushed by a speeding train as they travelled southwards toward Chilika. Lakshmi’s herd waded through the river Mahanadi, across towns,villages, industrial areas and highways to reach Athgarh.

Elephants chased away from their home, chased everywhere, trapped in forest scraps. Untamed, cornered, desperate. Pushed into conflict with man, they have retaliated, killing people.

Elephants chased away from their home, chased everywhere, trapped in forest scraps. Untamed, cornered, desperate. Pushed into conflict with man, they have retaliated, killing people. Yet, they “listen”, and respond to the squad, who are, literally, their shadow.

Why? I ask the Athgarh squad.

The answer is as simple as it’s complicated: “The elephants know we help them,” said Sanatan.

They have warned electricity department authorities of sagging power cables—an easy, frequently used weapon to kill elephants. Elephants are felled by sagging power lines—which may be accidental but avoidable. But many times it is deliberate poaching or retaliatory killing by live wire traps and electrified fences.

In Odisha alone over 60 elephants have been electrocuted in the last five years, according to data compiled by the Wildlife Society of Orissa based on forest department records and newspaper reports.

Panchu and his group have even rescued Lakshmi’s five-year-old calf, called Nungura ( “the one who teases’’), because he is a bit of a brat, naughty, curious, whimsical. “Actually not unlike my own son, Pintu,” mutters Panchu as his mates holler in glee. Nungura had fallen into an open well. The calf shrieked, flailed in the depths, as the herd desperately tried and failed to lift him out with their trunks. The inevitable crowd gathered. Curious—and suicidal—onlookers who tried to get close to watch the tamasha were charged at by an enraged, distressed Lakshmi. A few came particularly close, unmindful, even mocking the elephants, mobiles held aloft to click selfies. Lakshmi charged, stopping just short of them. She bellowed in warning, once, twice, thrice; maybe more, but heedless, the men jostled ahead, peering into the well. Tormented by the crowd, and terrified for her calf, Lakshmi struck, killing one man.

The situation was rapidly getting out of hand, if not becoming explosive, when the squad arrived.

They admit to a brief moment of fear—after all Lakshmi had just killed a human—before it flickered out. “The elephants were not killers. They will not harm intentionally. We knew it was only because she was provoked, cornered, and like all mothers, fiercely protective.”

“So we talked to a distraught Lakshmi, calmed her, reassured her that we would get back her child…only she has to let us do our job,” says Panchu. The matriarch moved away, a silent sentinel, as with the help of an earth mover, the calf was rescued and united with the herd.

In the alien, hostile world that the elephants have been tossed into, they know that they have these men on their side.

Such bonds and elephant behaviour, while extraordinary, is not unheard of.

Elephants are one of the most intelligent of animal species and are adept tool users. They fashion twigs to shoo pesky flies, use logs to break electric fences designed to keep them out, and have strong social and familial bonds. They are sensitive and empathetic, and comfort one another in times of distress. When threatened, adults in a group close ranks, get into a huddle, encircling and shielding babies with their bulk. In north Bengal, five elephants were mowed down by a speeding train in 2010 when trying to save two of their young trapped on the Siliguri-Alipurduar track. In Corbett National Park, a mother carried the wasting body of her still-born calf for days, constantly touched and caressed by others in her herd in an effort to comfort her.

Photo: Aditya Chandra Panda

They co-operate and coordinate to solve problems, understand and respond to people. Researchers in Amboseli, Kenya, speak of individual elephants recognising them after a gap of 12 years. In Assam’s Manas Tiger Reserve, guards recall that elephant herds would gravitate toward their quarters during the period of insurgency, which saw brutal violence and poaching. Did they feel safer? We don’t know—but in times of peace, such behaviour diminished. A severely dehydrated tusker in Uttarakhand allowed forest officials and vets to help him—even pour gallons of glucose down his throat. When better, he calmly walked away, as his rescuers stood by.

While these seem anecdotal oddities, science supports the idea that elephants are intelligent, social, empathetic beings with a problem solving ability.

At Athgarh, this man-animal relationship is taking a toll on the trackers. Their affinity to the elephants has alienated them from the other village folk, at times even their families, who bear them a grudge for the loss of crop “their animals” have caused, and the havoc they create. A few locals also find this the perfect pretext to strike back for being caught by the watchers/trackers for poaching deer and boar for the pot.

Sanatan says his father is fed up and fears for his son who faces the community’s wrath. He offered to pay Sanatan the ₹200 a day he gets as wages, if he left the job, and the elephants alone.

But Sanatan won’t leave his job. Like the rest of the squad, for better or for worse, he feels bonded to the elephants.

It wasn’t always so. Their employment in 2011 was triggered by the escalating human-elephant conflict. Panchu and gang were unacquainted with elephants, their impression of the animal largely based on the stories of conflict and confrontation. They were apprehensive and clueless. In the beginning they followed the elephants at a “very safe distance”, joining the crowd in bursting crackers, lung power and loud bangs, in an effort to scare them away.

It didn’t work. In fact, it had quite the opposite effect. The uproar spooked the animals, leading to greater chaos and damage.

The turning point was when they realised that the elephants were as terrified as they were. “We also sensed that they didn’t misuse their immense strength, their power—they could have actually caused us grievous harm, as we bumbled behind, trying to chase them away,” said Panchu. “This gave us courage.” And sparked in them a feeling of empathy for the beleaguered pachyderms.

In the mornings they try and trace the elephants to keep tabs on their location. By afternoon, they have a fair idea of where the elephants are and also an idea of where they will move—which villages will fall in their path that evening. Most wild animals usually take set routes—they work out the best ones and stick to those. Most of the time, the squad watches over their herd until the elephants are safe in the next fragment of forest.

And as they monitored their charges round the clock, they learnt about elephant behaviour, and individual characteristics. They identified which one was unpredictable, which one calm. They knew that Lakshmi was gentle, yet aggressive. As the matriarch responsible for her herd, she would put her life at risk, and kill others if she felt threatened. They learnt it was hunger and thirst which drove the elephants. And they saw them grieve. When one of the elephants was electrocuted, the herd tried to rescue the dying elephant , trampling the live wire and getting hurt in the process. They surrounded the carcass, circling it, touching it, shaking their heads back and forth, calling out in distress.

Photo: Aditya Chandra Panda

And so, the fear factor fell—on the part of both man and beast. The elephants started recognising them, even seeking them out among the crowd when surrounded by mobs. It motivates them to go on against all odds, say the trackers. It’s certainly not the money, the wages are low. All of them have other means of livelihood. Panchu, for instance, runs a small farm supply shop, the rest supplement their income with their small landholdings. Tackling conflict situations is stressful, at times risky, and knows no hours or Sundays. While their kith and kin celebrate Diwali and other festivals, the squad steps up its vigilance during festivities, with the accompanying noise and crowds. Nights are when the elephants are most vulnerable: to open transmission wires or around train tracks.

However, even such monitoring and dedication cannot be a solution to the issue of human-elephant conflict, unless the root of the problem—vanishing, fragmented habitat—is addressed. Loss of forest cover directly causes, and increases conflict, as the experience in north Bengal shows. At least 50 people have been killed in the two districts of Jalpaiguri and Darjeeling. The elephants have lost nearly 70 per cent of their original habitat in the region, which has been occupied over the years by tea estates, labour lines, fields, defence infrastructure, hydel projects, highways, rail tracks, resorts, etc .

Elephants have been killed as well; many bear scars, burns from lighted mashals, their bodies limp and pockmarked with bullets. It wounds the spirit as well. Calves born in, and living with conflict are not unlike children raised in war zones. Anxious, traumatised; and having never known peace , they are more prone to get into conflict situations. The conflict mitigation team here is the “Mal Squad”(based in Mal Bazar) and was set up in 1979, the oldest such in the country. It receives no less than 50 distress calls a day. At best, squads such as these can defuse the crisis—but it’s not unlike applying a band aid to a festering, bleeding wound.

In Athgarh, the sliver of forests in which these 25-odd-elephants are confined, cannot sustain them. As instincts dictate, the animals have tried to get back to their original home range, Chandaka, but were obstructed by barriers—moats and walls built as part of management plans by the forest department. The elephants were turned away, from a sanctuary created to protect them.

Even the fragments they inhabit now in Athgarh are threatened. Grassy meadows which the pachyderms prefer, are being plotted, concretised and built upon.One of the critical water sources, a natural pond is slated to be filled up for a ‘Picnickers Paradise Park’.

No one bothers to consult the squad when an elephant habitat or a crucial waterhole is signed away for a power plant or a shopping complex. The trackers form the lowest rung. In fact as contract labour, they do not even exist in the official hierarchy of the forest department.

In a state which has forsaken its elephants, this “squad”, and others like it in similar conflict hotspots across the elephant range, are the animals’ only saviours.

The state government has overseen the destruction of critical elephant habitat and corridors; in fact, it even refused to notify two proposed elephant reserves—South Odisha and Baitarani Elephant Reserve, in deference to mining interests.

This landscape is rich with elephant lore. Historically, the elephants of these jungles were the most coveted for wars. About 50 kilometres from Chandaka is the ancient elephant sculpture at Dhauli, where the emperor Ashoka embraced Buddhism, and ahimsa.

In India, the Elephas maximus is strictly protected by law and is listed under Schedule I of the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972. It is also accorded the status of our Natural Heritage Animal.

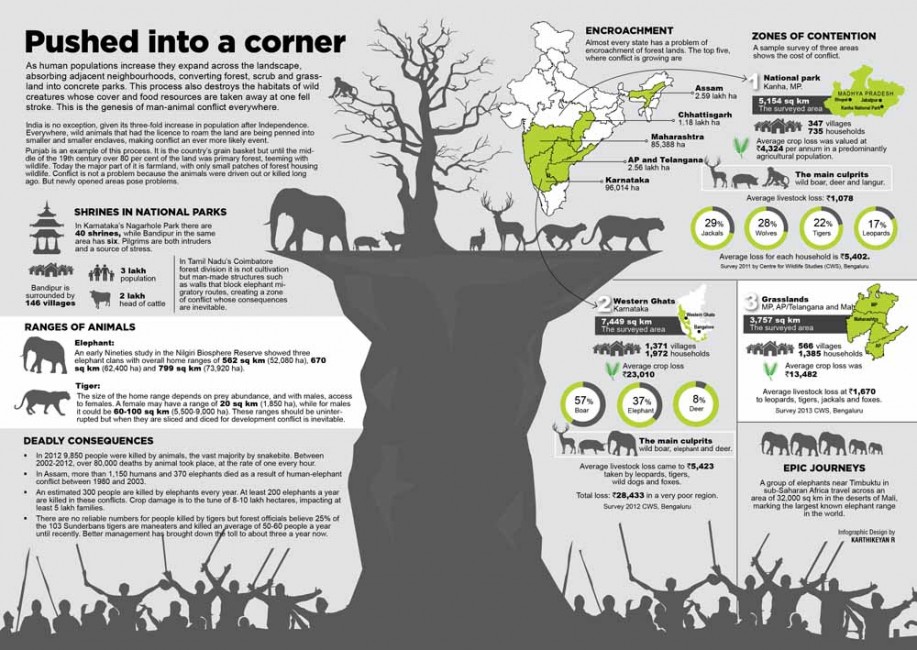

The turmoil and the conflict at Athgarh is a microcosm of what is happening across its range as forests and ancient pathways of elephants are decimated, drowned and destroyed by urbanisation and development. Human-elephant conflict has escalated across its range, with fatal consequences to both sides—all over India about 300 people lose their lives to elephants annually and many elephants are felled in conflict.

The central government also failed to act on the recommendations of the Elephant Task Force it appointed in 2010. One key recommendation was to create an empowered National Elephant Conservation Authority along the lines for the tiger, but it was dismissed. While some cosmetic recommendations like the Haathi Mera Saathi (the title of a popular yesteryear Bollywood film) campaign was started, substantial recommendations of bringing crucial elephant habitats and corridors under some kind of graded legal protection was not taken on board.

Currently, only a third of elephant habitat is covered under the Protected Area network. This is not accidental. The elephant habitat is also prime coal and iron-ore land.

In Betakholi, Athgarh, dusk has fallen and elephants have broken cover. The squad readies to watch over their herd, now a little too close for comfort to the village. I wonder, worry about their future, grapple for a solution to this complex and arguably hopeless issue. I look to our ‘elephant men’ who say that it is not the elephants who are the problem. “Elephants are wise, intelligent, peaceable beings with a heart, a conscience. We have wreaked havoc in their lives—taken their home, their food, blocked access to water. We have killed their families, destroyed their society. So they are pushed into being something they are not—aggressive, erratic, belligerent. Whatever “solution” we think of, has to keep the elephant in mind. Only then there is hope,” they say.

With Inputs by Aditya Chandra Panda

Prerna Singh Bindra is a conservation journalist. She is a former member of the National Board for Wildlife.