Eliminating Makhana from Bilkurul Beel

Bilkurul Beel (Beel: a large body of water) in Murshidabad district, central West Bengal, is a large wetland, seasonally connected with a channel of Bhagirathi. It supports significant biodiversity, including important species like Fishing Cats and Otters which are a part of Schedule I of Wildlife Protection Act (1972). It is a repository of threatened indigenous fishes, which are fast depleting across the region. It hosts a large number of birds, including some 5-10 thousand migratory ducks in winter. About 600-700 families of fishermen, living in three villages around the wetland, depend on it as their sole source of livelihood. Farmers around the Beel use the water for irrigation.

Makhana cultivation: a novel and illegal enterprise

Bilkurul Beel was leased to a fishermen’s cooperative for fishing alone. However, around mid-2021, outsiders, funded by some locals, began cultivating Makhana in Bilkurul Beel with the help of an illegal permit issued by the Gram Panchayat.

Due to its growing demand, cultivation of Makhana (Euryale ferox) is a lucrative activity. It happens on a large scale in Bihar. However, in Gangetic West Bengal’s Murshidabad, it was a relatively novel practice. Moreover, it was at odds with the fish-dependent economy of the large fishermen community living around the wetland.

The ensuing environmental and socio-economic catastrophe

Cultivating Makhana gives exceptional returns but devastates the wetland in the process. The cultivation utilises an unhealthy amount of weedicides, fertilisers and other agrochemicals, which render the water toxic and unusable.

Further, the enormous leaves of the mature plant cover the entire water surface, preventing sunlight and oxygen from entering the water and making it difficult for waterbirds to settle on the surface. Additionally, the Makhana plants replace the native aquatic vegetation, vital for sustaining life in and around the Beel.

With the onset of illegal Makhana cultivation, the Beel began undergoing the changes described above, adversely impacting the life present in the wetland and the people dependent on it. Fish populations started declining due to oxygen deprivation and high chemical toxicity. Waterbirds were deprived of foraging and roosting opportunities; thus, their numbers also began dwindling.

Fishermen could no longer find fish in the water and contemplated relocating to a different place. Additionally, they had begun developing ailments, particularly of the skin, due to using the polluted Beel water. With rising health issues and no livelihood to bank on, fisher communities were severely hit. Farmers, too, were at risk. During monsoon, the polluted water could leach into the nearby cropland and the Bhagirathi river, adversely impacting crop yield.

The repercussions of Makhana cultivation in Bilkurul Beel were consistent with the after-effects documented in a study conducted by Jadavpur University between 2003 and 2005 across various wetlands in Malda district, where Makhana cultivation had been briefly attempted.

The fisheries department in Malda eventually ended the cultivation in 2005 after an outcry by locals, mainly the fishermen. However, in Bilkurul Beel, support from more influential quarters ensured that the cultivation continued despite entire villages losing their livelihood. There are now signs of this practice spreading to other wetlands of Murshidabad and Malda, most significantly a nearby Important Bird Area (IBA) called Ahiron Beel.

Our intervention

Taking notice of this problem, HEAL decided to intervene, and we took the following action:

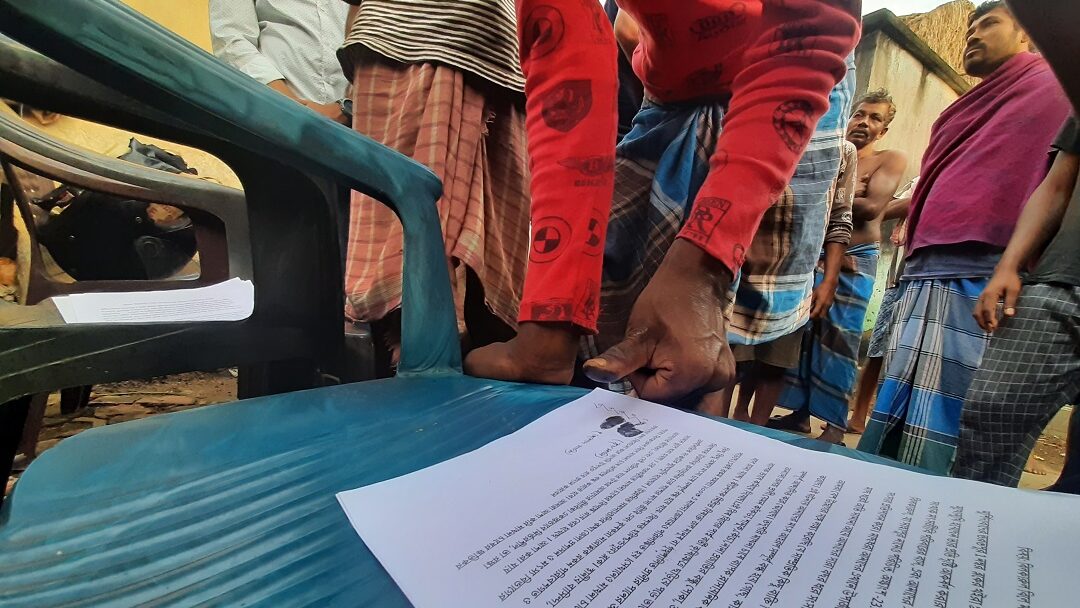

- In September 2021, we conducted an on-site assessment comprising photo documentation of the Beel and interviews with locals to assess the nature and extent of the problem. The locals testified how the cultivation had negatively impacted them, and we realised that their goals completely aligned with ours – to rid Bilkurul Beel of the Makhana monster.

- We ran a mass signature campaign, and within a few hours, we gathered signatures of 112 fishermen families from three villages. We notified the forest department of the issue and approached the district authorities, who ordered the gram panchayat to clear the Makhana plants from the wetland.

- During January 2021, we led a water bird census at Bilkurul Beel with the forest department. Slight improvement in the health of the Beel as a result of a temporary halt in the cultivation was observable. We documented over 3600 waterfowl and the highest congregation of Garganey in the entire West Bengal at the Beel.

- Around the same time, Makhana seeds were spread again, and plantlets soon sprung up. The cultivation resumed again illegally and the Gram Panchayat did nothing to stop it despite being ordered. Tired of inaction, in February, we organised a clean-up of the Beel. We received support from the police and administrative authorities while the local fishing communities volunteered to participate in and carry out the clean-up.

This project is unique, in the sense that, it ties the interest of the local fisher community with habitat conservation. We were overwhelmed by the support we received from the villagers near Bilkurul Beel, and we hope to use this alliance efficiently to rid the bilkurul of this multiheaded monster.

Re-emergence of the problem and future course of action

As of mid-2022, makhana cultivation was restarted and by June, a significant area of the wetland was covered with Makhana plants. If the Makhana plants are not removed, their leaves will again layer the water surface, preventing waterbirds from settling on the water.

Therefore, we have documented the re-growth and initiated dialogue with the district authorities to seek prompt action before the winter migration starts. In addition, the wetland is currently being monitored with the aid of local fishing communities.

So the fight is far from over, and we have a challenging issue at hand. However, we are determined to save this fantastic wetland habitat and will try out all avenues, including legal action, if necessary.